We’ve previously written about designing services that make positive choices possible for achieving net zero.

Given 90% of homes and most vehicles are owned privately, it will be citizens and businesses that need to change the way we travel and heat our homes. Supporting behaviour change and the adoption of low carbon solutions at scale is essential here.

Despite this, a focus on technology over people means current policy is modelled on assumptions, focused on technical solutions, and disconnected from what is needed to encourage action on the ground. This gap between how net zero policy is designed and what people need to make changes poses a critical threat to the UK achieving its climate targets.

There is an important role for service design to understand the needs of citizens and organisations, with a more practical approach to policy development.

The current approach to net zero policy

Carbon pollution from burning fossil fuels is primarily responsible for global warming. Net zero is a policy response to climate change that aims to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases we produce and balance emissions with ways of removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere through natural sequestration.

The UK’s net zero strategy is focused on transport and energy because the transport and energy sectors are responsible for 83% UK emissions. Our net zero targets are legally binding government commitments to ensure the UK reduces greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2050.

Four key principles underline how the UK’s net zero strategy is designed, ensuring:

-

consumer choice, so that no one is required to rip out their boiler or scrap their car

-

the biggest polluters pay the most through carbon pricing

-

the most vulnerable are protected through government support

-

businesses will be able to deliver cost reductions in low carbon tech to bring down costs for consumers

National targets include things like:

-

no gas boilers in new build properties by 2025

-

ending the sale of petrol and diesel cars by 2035

-

fully decarbonising the power system by 2035

The challenge of how net zero policy is designed

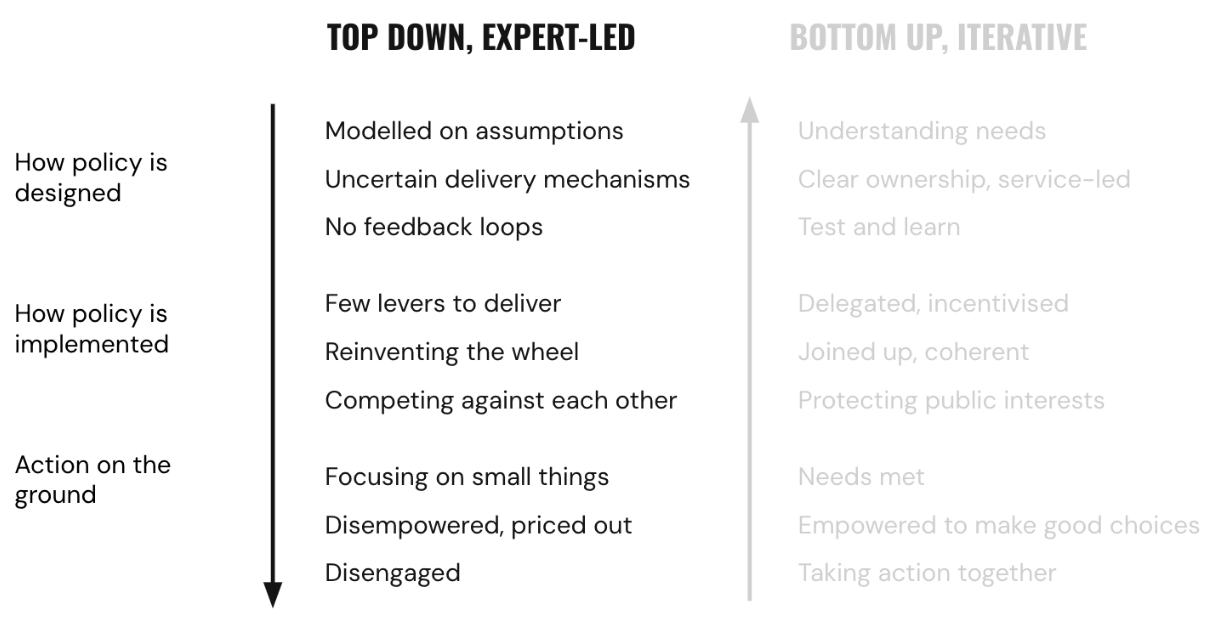

A disconnect between how policy is made centrally and what people need in practice is a huge barrier to achieving Net Zero. A top down approach to policy making means government teams planning and setting rules, based on theory and technical models, often lack clarity about how this will happen in practice.

National targets are set and divided between Local Authorities as targets for their area based on regional demographics, economics and geography. It’s then up to councils to create their own climate action plans – often through a mix of adopting national targets and developing their own strategies based on local priorities and engaging with communities.

Variation from area to area is dependent but in many places you’ll find a commitment to cycling, walking, nature, energy efficiency, green jobs and green industry. Some places, like Bristol, are ahead of the curve with bold innovations like Bristol City Leap which will invest nearly £500 million into low carbon energy infrastructure.

Why a top-down, expert-led approach is failing

1. Policy and targets modelled on bad data

Traditional waterfall approaches mean the focus is on trying to use data and modelling to predict all the answers up front. Options are ‘stress tested’ digitally, rather than by running experiments in the real world and setting up feedback loops to collect evidence that helps us learn about what works, monitor progress and improve policy over time.

A general lack of high quality, available data means there are high margins of error in this modelling. This is exacerbated by how new net zero is. Many solutions have not been delivered at scale and we lack historical data to draw evidence about, for example, how quickly they might be adopted.

2. Historical focus on developing technology, not user adoption

Until now, the bulk of climate investment has gone into research and development of new technologies that can support us to reduce emissions, such as solar and heat pumps. Now these technologies are market-ready, the new challenge is scaling solutions so that unit prices are lowered and they become more affordable to the public.

However, in policymaking, we haven’t caught up with or reframed these new challenges. This means we aren’t always considering how solutions will be scaled through new services and business models. We aren’t incorporating enough evidence or insights from citizens and the supply chain into policy design.

3. Technical silos and a lack of diverse skills

The focus on technology over user adoption means there is a high concentration of people with legacy skill sets, in areas like infrastructure and engineering, working on climate policy. While there is a drive to consider how some digital skills such as AI and data engineering might help develop net zero policy, we’re lacking the diverse skills needed to understand how we drive behaviour change and adoption of these solutions at scale.

A focus on implementing solutions instead of designing services means technical teams work separately on different policies. This results in disjointed and sometimes conflicting efforts to roll out, for example, heat pumps and hydrogen – which is confusing and difficult for people to navigate. We should organise government teams around the problem of decarbonising homes and buildings so that efforts to help citizens and businesses consider which option is best for them were coherent and coordinated.

4. Local areas don’t have levers and support

A focus on modelling over needs means the lack of levers or funding that local government needs to encourage action is overlooked. If we take housing as an example, over 90% of buildings we will live in by 2050 already exist and less than 10% are publicly owned. This means incentivising supply chains and households to retrofit their properties is critical.

With the existing financial pressures and growing demand for services that councils face, their new responsibilities for net zero delivery will need central government support to invest, innovate and work together. Instead, funding mechanisms encourage local authorities to compete against each other for short term funds to reinvent solutions that often already exist, rather than sharing knowledge.

5. People being disempowered and disengaged

As we’ve found in our user research with households and business owners, this results in people feeling disempowered. The technology solutions championed by national and local strategies seem prohibitively expensive. For firms and supply chains, the demand is not sufficient to invest in taking technology to the mainstream. It means the public narrative around net zero is either very negative, or focused on the small things we can control – like recycling or shopping second hand.

How service design can help us learn what works in practice

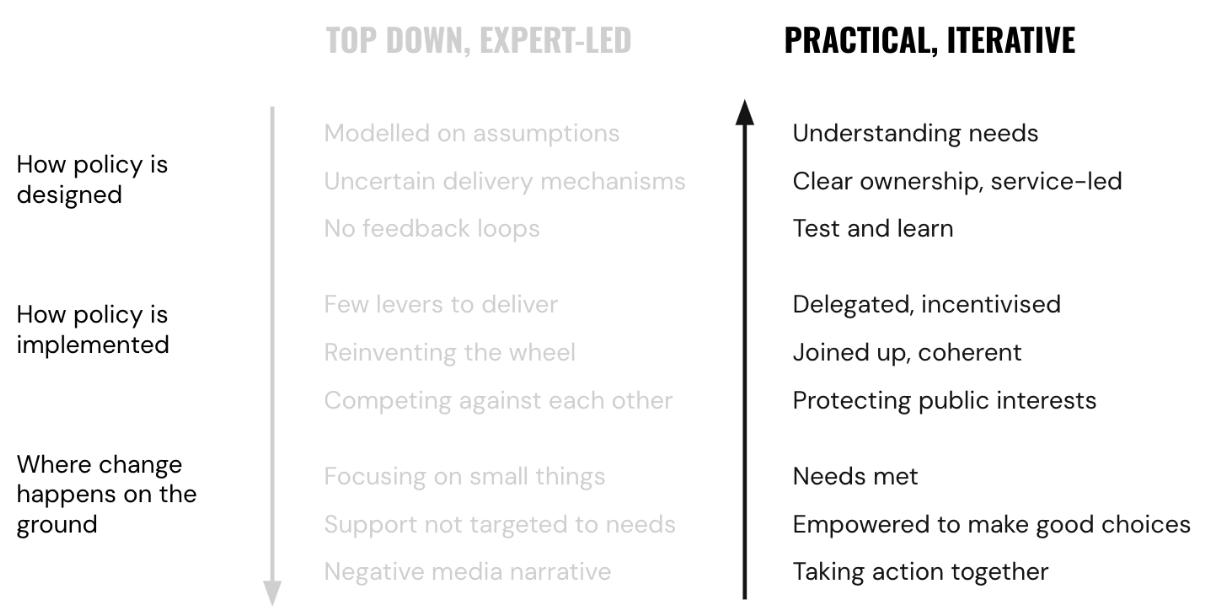

By contrast, service design approaches can help net zero policy succeed.

By focusing on the needs of the people and organisations that will have to take action to reduce emissions, we can design policies with the appropriate levers and incentives that make the switch possible. Prototyping services as part of the policy design process can help bridge the gap between policy and delivery, providing live feedback mechanisms about what does and doesn’t work, generating the evidence we need to design and implement new policy with confidence.

In our recent work, we applied the following service design principles to bring policy, digital and delivery teams together and shift to a more practical, iterative approach to net zero policy making.

Understanding needs to design and communicate a value proposition

Low awareness of net zero solutions or false assumptions about their downsides is a major barrier to adoption.

Policymakers often assume that the public won’t be in favour of measures designed to curb emissions, leading to caution about openly communicating changes that are coming. Often, however, the value proposition of net zero solutions for people and businesses is poorly defined, and so little is communicated or understood about their benefits.

For example, people managing public and commercial buildings need to know if connecting to a heat network is their cheapest option for switching to low carbon heat. While a local authority might need to know how different solutions can help them meet their climate targets at scale.

There is currently a lack of accessible information about net zero solutions from trusted sources. Particularly, information that helps people prepare and take action at home and in their organisations. Communicating timelines and when people can expect to see, for example, a heat network in their town, standards for EV charging points or legislation that protects consumers from exploitation, is key to building confidence in switching.

Understanding systems and who will play what roles

Service designers can help move beyond theory, and map out how policies will work in practice. The first step is identifying key actors — for heat pumps, that might be government, councils, heat pump suppliers, manufacturers, investors, building owners and citizens — and mapping the transactions that will happen between them. This helps show who is involved and what future services could exist to help those transactions happen more easily.

For instance, if councils are expected to consult their communities on proposed locations for heat networks, the government could provide a service that makes it easy for them to understand that consultation process, and how it can be incorporated into local planning. If building owners are expected to install new heating systems, there could be a service that helps them check what options are best for them, when they should carry out work and how much it might cost.

Bringing people together across policy, digital and delivery teams to discuss and iterate system and service maps often reveals inconsistencies in the way different stakeholders imagine policies and different assumptions they have about who will play what role. It shows the scope of decisions that need to be made and prompts important discussions about the purpose of a policy and whose needs are a priority.

Bringing future user journeys to life

Service design methods are useful in showing what a policy might look like during delivery. Visualising the future in terms of journeys for different users can show gaps in thinking and help influence decisions according to what people might need to fulfil their expected roles. Using a ‘policy backlog’ tag to mark all the decisions that a policy team needs to make about how the roll out of, for example, heat networks is going to work helps policymakers organise the policy timeline according to the decisions that need to be brought forward to meet the immediate needs of critical users.

Service maps also surface dependencies and the sheer scale of action required to deliver complex policies aimed at scaling the adoption of new low carbon technologies.

Prototyping to test and learn

Finally, prototyping services – by testing individual service components or running stakeholder meetings – are essential to testing riskiest assumptions about how a policy will work. Experiments that test new ways of working can provide rich and reliable insight into potential enablers and barriers.

In the early stage of the policymaking process when there is so much yet to be decided, government teams can feel understandably nervous about prototyping. How will the policy be received? What if it backfires and people react badly? What if we give away sensitive information? But with careful preparation, prototyping and testing is also a way of building trust. It can show that government is listening and open to working with people to understand, and better respond to their needs.

Taking a service based approach to policy design

In the last few years, we’ve seen a shift towards recognising the important role that design can play in the policy space and we’re proud of what the government teams we’ve worked with have achieved in spite of the challenges they face in implementing this kind of policy approach.

Supported by service design, a test and learn approach to policy focused on the needs of people and organisations can help us identify the services and initiatives to drive adoption and ultimately shape the success of a policy area as important as net zero.

If you’re interested in exploring this work further with us on delivery net zero, get in touch with Harriet Pugh.

Our recent design blog posts

Transformation is for everyone. We love sharing our thoughts, approaches, learning and research all gained from the work we do.

Lessons learned from joining projects in progress

We share tips for joining a project where there’s already an established design team in place.

Read more

Find out all about what our Design team has been up to over the past few months.

Read more

Em reflects on how we support large organisations to build confidence and embed approaches to support research activities.

Read more